Ayn Rand rocked the literary world with her anti-altruist writings. In particular, her epic novel Atlas Shrugged gave full berth to her philosophy, Objectivism. In said novel, the ultimate protagonist, John Galt--a figure who is intitially so enigmatic his name becomes a byword--questions, indicts, and redefines the very nature of humanity. Galt's soliloquy toward the end of the book drives a proverbial knife into the heart of modern Western values; he attacks their religious root, specifically located in the doctrine of original sin.

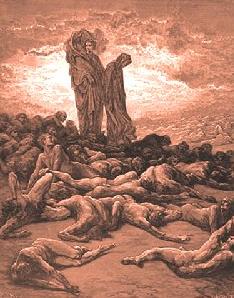

Ayn Rand rocked the literary world with her anti-altruist writings. In particular, her epic novel Atlas Shrugged gave full berth to her philosophy, Objectivism. In said novel, the ultimate protagonist, John Galt--a figure who is intitially so enigmatic his name becomes a byword--questions, indicts, and redefines the very nature of humanity. Galt's soliloquy toward the end of the book drives a proverbial knife into the heart of modern Western values; he attacks their religious root, specifically located in the doctrine of original sin.As quoted from Galt's speech, original sin is an impossible reality that "begins by damning man as evil, then demands that he practice a good which it defines as impossible for him to practice." Original sin, as set out by the first Christians, however, suggests that human beings are deprived of their natural connection to God because Adam and Eve, humanity's representative couple, disobeyed God thereby setting all people forever at a distance from their Creator. Thus Adam and Eve, and everyone after them, suffer the burden of godlessness--the void between God and man--which is hopelessly incurable except by the movement of God across that void. And, as Christians claim, God spanned that void in the person of Jesus Christ.

Everyone born into the world then, according to classic Christian formulations, inherits the burden of being simultaneously in God's image and likeness (Gen. 1:26-27) and also separated from God by original sin. Rand's vicarious observation that the Christian "code" damns man for his godlessness and then demands man be good--which is to say that man is to be godly--points at a fatal flaw in Christian conceptions of the nature of man. Namely, if by original sin man is unable to be godly because of his godlessness, why condemn man for living in the condition he was predisposed to?

That man was created 'good,' even 'very good' (Gen. 1:31) is simply a nod to a time well behind him. The post-Edenic reality is that man is "evil" (Matt. 7:11) and exists in a subordinated position; a position that does not act on his innate inclinations of being a free, noble creature but binds itself to the self-deprecating notion of being "depraved," or "distorted," or "disordered." Man, to be 'good,' must first lie to himself that he is, in fact 'bad,' will himself to believe his lie, and then plead the pity of the Creator who would save him from himself.

From the start, man is damned, if not by his own belief that he has to lie to himself to set up the conditions for salvation, then by the inheritance of representative man's sin (through Adam and Eve) which places him at odds with God. In essence, man is damned if he does, and damned if he doesn't.

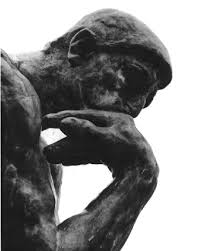

How could anyone get on with such of wave of contradiction and catch-22's? How could anyone understand their place in reality, their identity as a human being, given such misfit logic? Clearly,

"It does not matter, the good is not for him to understand, his duty is to crawl through years of penance, atoning for the guilt of his existence ato any stray collector of unintelligible debts, his only concept of a value is a zero: the good is that which is non-man."According to such a "monstrous absurdity," original sin means man is not 'good,' he is evil (cf. Matt. 7:11). Since a double-bind is placed on man--inherit a sinful condition and/or commit evil by lying to oneself and therefore make yourself evil--his whole moral condition, the opportunity for will, his very freedom is predetermined for him. Man has been deemed guilty without his choice even before he exists.

There is no sense in that conclusion, obviously, but that is what the doctrine of original sin requires a person to believe for it to have any psychological hold. A person cannot be bound to a creed that has no discernable impact on his psyche. No-one is passionate about the banal. No-one is driven to deliver themselves from ineffectual and meaningless propositions. Such things are easily discarded by the very act of choosing to.

For a concept to lay hold of a person fully, and to generate enough fervor that he is irrevocably compelled to seek salvation from the subjective realities of that concept it has to strike hard and deep at the core doubts, fears, and needs of a person; it must demean a person's sense of life and moral confidence.

Original sin does just that.

So this begs the question: is the 'Freedom From Religion Foundation' fundamentalist? Do they preach a dogmatic version of atheism? It would seem from their inelegant bus signs that they consider themselves fully in command of what is right, of what is true. Namely, that faith is beneath human dignity, that we should

So this begs the question: is the 'Freedom From Religion Foundation' fundamentalist? Do they preach a dogmatic version of atheism? It would seem from their inelegant bus signs that they consider themselves fully in command of what is right, of what is true. Namely, that faith is beneath human dignity, that we should