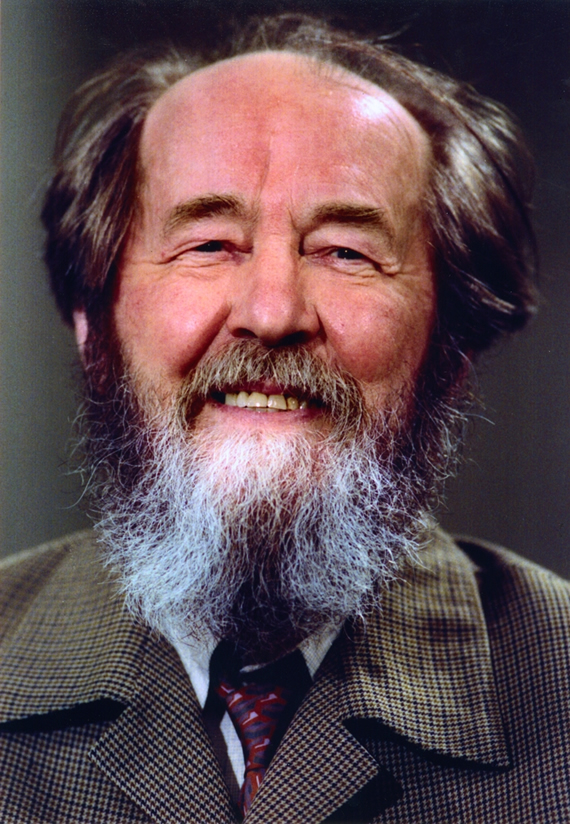

Gregory Boyd

Gregory Boyd. He's a man of great learning, insight, and dedication. A former atheist, he became a Christian in 1974, and eventually gratuated from Princeton Theological Seminary with a Ph. D. He's a formidable philosopher, a top-notch theologian, author of many scholarly and popular books, a former professor of theology, and currently a pastor at

Woodland Hills Church in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Lately, I've been reading through some of the material on his site, Christus Victor Ministries, and came across a very important article I think every Christian should read. It concerns women in ministry. It's a hot-topic, to say the least, and has been for quite some time.

Now, given my background in conservative Lutheranism, I was once a staunch supporter of the 'men only' policy toward ministry positions. Women, I believed, were wonderful, beautiful, and spiritually gifted individuals who -- for reasons that were suspicious to me then -- were disallowed any ecclesial teaching office. Since I was ordained a Rev. Deacon, and was training in seminary to become a pastor, I wasn't prepared at the time to challenge the status quo. Most especially because it would mean expulsion from seminary, and a definite case for church discipline where I was serving.

On a more personal note, I am married to a tremendously erudite, and sagacious woman (Sarah, co-author on this blog) who, despite her many and profound giftings, was prevented from using those giftings (which extend beyond her natural ability to nurture our children, and cook food) because of her status as a woman. To Sarah's credit, I probably wouldn't have done as well as I did at seminary were it not for her incisiveness, natural knack for making theology practical, and her superior ability to converge disparate, abstract pieces of information. In many ways, any success I have ever had as a teacher, church servant, and communicator is due to Sarah's ministrations to me, and our family.

Given what I've just written -- that I was always suspicious of the 'men only' dogma, and that Sarah has many extra-domestic talents and giftings -- it became a matter not just of curiosity, but of necessity for me to start asking important questions like: why shouldn't my wife, who is a more capable teacher than me, have the opportunity to teach? What biblical warrant is there for Sarah to have to suppress her God-given abilities? And wouldn't that be contradictory? Or, as Sarah once put it, "why would God give me these gifts and then make it so that I'm disallowed using them?" These kinds of questions apply across the board, really: why would God create women to have the same spiritual and intellectual gifts as men, declare their total equality to men (Gal. 3:28), and then proscribe their use of those gifts? Is God capricious? Is He fixed on torturing women's psyches? What's the deal here?

As I said earlier, it became a matter of necessity to have these questions answered. And the answers didn't come fast, or easy. In fact, I agonized over this issue for many years. I was torn between wanting to keep my loyalties to those men of God that I loved (Rev. R.A. Ballenthin, and Dr. William Mundt), the Scriptural declarations that seemed so precise and clear (esp. 1 Tim. 2:11-15, and 1 Cor. 14:34-35), and the fantastically gifted woman I married. All of this came to a head when I took two years away from church (a wonderful catharsis for my wife and I, but not something I would necessarily prescribe as a common course of action).

During those two years in absentia, I grew more sensitive to the arguments proposed by my wife, and other scholars that certain passages of Scripture were more culturally relevant, or contextually skewed due to lack of appropriate cultural references in our present day. I didn't want to bite this bullet, as it were, because it seemed so hackneyed, so oft-parrotted that I didn't want to re-visit the philosophical implications it presented; I had already dismissed such ideas in my seminary days. God's Word was God's Word, and it contains no errors. And in this case, I still believe that God's Word contains no errors: it says what it means about women in ministry. The problem was that I wasn't understanding what Scripture meant by what it said. So, because of that, I was forced to chew back my (then) cynicism on the issue of 'cultural relevance', and re-visit the issue.

Fortunately, my wife and I came into contact with a house-church couple who invited us to participate with them in worship from the home. Eager to have fellowship, we accepted the invitation. But it quickly became apparent to us that this couple was living out to a much greater, and to a much more shameful level, the same 'men only' policy that I was struggling with. As I observed them and asked some questions, their understanding of Scriptural warrant for silencing women reflected the extreme logical end of the same understanding I had ruefully carried about for years: women were out-of-place teaching in church. For them, however, the extreme expressed itself in complete and utter disallowance of women to speak at all during times of worship. In fact, the one time I witnessed this couple's teenage daughter speak, both her mother and father quickly turned on her and launched Scriptural condemnations at her as if they were taking target practice with a handgun. She was shamed, the father was red-faced with anger, and her lively eyes dimmed into sadness.

So how was that experience 'fortunate'? Simple: it put a bold-faced stamp on the absurdity of over-extending ancient cultural imperatives into present-day scenarios. To put it differently, I learned that day that it is of paramount importance to re-examine our cultural differences now that we're 2000 years removed from the ancient biblical world. Sometimes there will be consonance. Sometimes there will be startling, and important differences. Seems like a simple, even obvious fact, doesn't it? But try learning that from the position of a pastor-in-training, who wants nothing more than to do God's will, and take care of his family. It isn't easy. And it took a total break from the pursuit of that vocation, that lifestyle, to even begin to have the opportunity to freely explore such an issue.

But I did. And here is where I now stand: I find it absurd that women are excluded from ministry positions. Not only that, I find the notion of religious 'authority' to be so illusory, and filled with shoddy, unbiblical reasoning that I can no longer justify the typical dyed-in-the-wool treatment of "no woman should have authority over a man" (1 Tim. 2:11). That pericope was an imperative leveled by Paul to a particular church, in a particular locale, at a particular time experiencing difficulties with certain rebellious tendencies. Paul, being the educated, and highly intelligent man that he was, I am quite certain of it, would have made a universal statement to all believers if it truly were God's will that no woman at any point in time, anywhere, and for any reason was to have a voice in the assemblies of God. It would be the height of imbecility and insanity to suggest that Paul intended a universal application of the 'men-only' policy when he quite consistently breaks his own policy in several other places in Scripture! It would also be egregious to state that Paul attempted a universal silencing of women when he wrote such passages as 1 Tim. 2:11 and 1 Cor. 14:34-35 when he was intimately aware of the ministry of women to Christ, Christ's elevation of women, and other Scriptural writings that showcase the importance of women in ministering capacities.

No. Paul intended to be particular in his application of the passages I've noted. To say otherwise, would be to misrepresent one of Christianity's greatest figures, and declare God a liar. Are you willing to go that distance? I'm not. I'm also not willing to make arbitrary, unbiblical distinctions the likes of which allow for women to minister in churches but only in nursaries, or to female 'tweens'. If you've agreed with me so far -- that women are equally ministers with men -- then such a cockeyed distinction is just another way to subvert the potential capacities of women in the church.

For some extra, more clearly explained material on this subject, let me refer you to Gregory Boyd's article "

The Case for Women in Ministry". It's an excellent read with a lot of fantastic points, and straight-up exegesis.

There's no excuse for not reading this book. You have to, and that's all there is to it. Chesterton is sheer genius.

There's no excuse for not reading this book. You have to, and that's all there is to it. Chesterton is sheer genius.

Gregory Boyd

Gregory Boyd