An erudite reader commented in a recent article that he was calling me (and another commenter) out on the term 'religion'. It was not an aggressive manoeuver, but a considerate action meant to help clarify conversation. Rather than leave it within the context of that exchange, however, I thought it appropriate to bring this subject up-front and centre, since it is a defining issue in so many people's lives.

So, what exactly

is religion?

Anyone can look around and note the various rituals, genuflections, processes, and events that religious people regularly attend to. But to note religion simply as a set of rituals and practices not only undercuts the driving importance of religious devotion, but it also relies on superficial observations of those things that are external to the religious anyway.

For example, everyone knows that Christians have a

cultus for the

sacraments, but that is where a good deal of understanding stops. It would require a little more effort to investigate the history, meaning, and respective differences in the sacraments, and further, the differences between varying communities of Christians. More effort would be required again to appreciate the aesthetic application of the sacraments to the religious life, and the nostalgic desire for transcendence that believers seek when they partake of the sacraments.

All this is to say that by observing that the religious have definite practices, we cannot then conclude that 'religion' is what we've observed: rituals, genuflections, proceses, and special events. Such a definition loops back on itself, and gets us nowhere. How much sense does it make to suggest that because we've observed people going to church and praying that religion is therefore going to church and praying? It doesn't make sense at all. All we have concluded with that kind of definition is that religion is what religious people do. The same logic is made memorable in the movie

Forrest Gump: "Stupid is as stupid does." It may be the case that religion is what religious people do, but no-one is the wiser for such a definition.

Our work is still ahead of us. Thankfully, many people have proposed definitions of 'religion' that cut a little deeper than a wistful glance at

Merriam-Webster. Here (thank you to

Dr. Irving Hexham) are

some of those definitions:

- William James: "the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto."

- Alfred North Whitehead: "what the individual does with his own solitariness."

- George Hegel: "the knowledge possessed by the finite mind of its nature as absolute mind."

James' definition approaches an appreciable definition of 'religion' but comes short; it only observes that people believe stuff and order their lives accordingly. I can observe the invisible quality of friendship just as much as I can observe the religious believing in an "unseen order". But observing friends being friends, or the religious being religious does not answer what 'religion' is anymore than noting that "stupid is as stupid does", as was mentioned earlier.

Whitehead's definition seems to dismiss the point altogether. People masturbate in solitude, but that hardly makes masturbation a religion. What one does when no-one is looking (i.e., in solitude) exorcises the very obvious fact that religion is a public phenomenon, a social event, a world-wide extroversion of beliefs. In this sense, solitude can be argued to work against religion; a social assent to a set of beliefs is quite the opposite to what one does in solitude, for what one does in solitude quite obviously lacks participation in public affiliations.

Hegel seems to want to relegate religion to a purely abstract realisation of the mind. That is, a singular, limited and mortal mind apprehending the fact that its essence, its very being, is unrestrained or unlimited; i.e., absolute. I think Hegel's definition anticipates his dialectic system more than a working definition of 'religion' proper. One thing Hegel's definition does intimate, however, is transcendence. This is helpful insomuch as it will aide in attempting a definition of religion later in this essay. For now, however, it is appropriate to note that one of Hegel's driving points was that the recognition of a boundary implies the possibility of going beyond it (which is the literal meaning of 'transcend', to go beyond). As such, for Hegel, religion is the implicit recognition that because a perceiving mind is finite, there must therefore be infinite, or absolute mind.

Where Hegel breaks down is in the practicability of his definition. Religion focuses on what is beyond the human condition, what is supernatural, and how those things can be invoked in human affairs. To state that a finite mind apprehending an absolute mind is 'religion' only tells us that religion is a recognition of a quality of being beyond our natural senses. That much is already assumed by the religious, though in far less philosophical terms. So Hegel's definition doesn't get us much further than to remind us that religion deals with the transcendent.

It seems we need to examine the original question again: what is religion? We have noted a few examples of what religion is not. Religion is not merely a list of things religious people do. Religion is not simply a lifestyle adjustment to an unseen order. Religion is not what you do when you're alone. And religion is not just an intellectual recognition of contrasts in reality.

Religion, it would seem, is quite hard to define. I think this is true in part because of its inherently vague gram matical application. Austin Cline notes that,

matical application. Austin Cline notes that,

"Definitions of religion tend to suffer from one of two problems: they are either too narrow and exclude many belief systems which most agree are religious, or they are too vague and ambiguous, suggesting that just about any and everything is a religion."

Saying 'cancer' is an umbrella term that connotes some form of auto-immune disorder. Similarly, 'religion' is a catch-all phrase that connotes the dispositions of certain groups of people toward a set of propositions concerning the supernatural. Then again, certain religious people (those who claim a 'religion') are not supernaturalists so much as they are idealists (e.g., some forms of Buddhism are described as atheistic; Mahayanic Buddhism comes to mind). Thus the word 'religion' can run us adrift of helpful understanding.

Some people consider the word 'religion' to be notional. It does not denote anything actual, or real. Jonathan Z. Smith writes in Imagining Religion:

“...while there is a staggering amount of data, phenomena, of human experiences and expressions that might be characterized in one culture or another, by one criterion or another, as religion — there is no data for religion. Religion is solely the creation of the scholar’s study. It is created for the scholar’s analytic purposes by his imaginative acts of comparison and generalization. Religion has no existence apart from the academy.”*

Smith's observation on the classification and definition of religion is keen and helpful. 'Religion' is a blanket term used to quickly, and easily categorize an area of experience and activity obvious in all human cultures. Given Smith's observation, using the term 'religion' at once expresses a common understanding without drawing attention to any one particular faith-claim (e.g., Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Bahá'í, et al.). But for the purposes of conversation, small qualifications are certainly needed. I would do poorly to speak with a Muslim about religion while not clarifying whether I am speaking in the context of his/her religion.

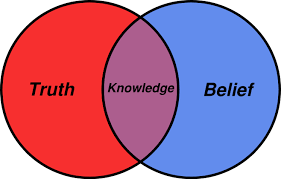

If the term 'religion' is a bit of a chimera made understandable by its attachment to academic generalizations, then whatever definition I give will necessarily enjoy the same attachment. Be that as it may, here is what I understand 'religion' is: the practice of specific, systematized cultural beliefs usually, but not necessarily, attended by the enjoyment of liturgical rites that anticipate communication with the supernatural, and invite an aesthetic experience of transcendence in the believing subject (person).

My definition is practical only in one sense: it finds a place in the academy Smith refered to earlier. Unfortunately, I don't think anyone can adequately define such a term as 'religion' without getting hung up on definitions that are too wide, and therefore fail to regard differences in varying religious claims; or definitions that are too narrow, and therefore inadequately refer to specific faith-claims.

Religion is a cultural motif. It is an on-going narrative that necessarily changes as the cultural climate changes. Some critics would argue that religion should determine culture (e.g., certain Christian academics feel this is an important action for Christians to undertake, and it is certainly a sentiment that runs quite deep within evangelicalism and American right-wing politics). Others argue that religion should be utterly removed from culture altogether by way of science, another blanket term (e.g., Sam Harris). Both positions on the nature of 'religion' in our on-going cultural narratives miss the point altogether: they are interdependent; we cannot force a religionless culture without removing culture and religion altogether. Both our culture and our religions provide an overarching story of our human experiences, aspirations, failures, growths and setbacks, and future history.

'Religion', as difficult a term it is to parse, is, despite its connotative nature, a very useful word that both binds and separates people, intimates a shared understanding, and provides many fascinating hours of stimulating contemplation.

*Smith's quote can be found in this article.

"In a criminal society, goodness is a crime. We have no moral obligation to tell the truth to the devil. To do so is likely to be actually immoral." --Dee

"In a criminal society, goodness is a crime. We have no moral obligation to tell the truth to the devil. To do so is likely to be actually immoral." --Dee